IMPROVE MY GAME

Articles

We Induce Failure: Therefore, Our Students Succeed

I've failed, therefore, I've succeeded. -Michael Jordan.

In my recent article on the influence of early specialization on youth development, I mentioned a philosophy that I commonly employ in my athletic clients’ training that centers on inducing failure. This suggestion has resulted in a large number of requests for additional information about how to structure such training programs as well as the rationale for training. In this follow-up article, I will review the benefits and limitations of “failure drills,” and provide the basis for the foundations of creating programs for your clients.

Failure is simply necessary for growth and development. Without it, the human mind will become complacent in its evolutionary progress. While failure is never the long-term goal, it is important to understand that through failure, players, coaches, and parents learn to identify areas of improvement, strengths to rely upon in the future, and most importantly, learn to break their “FishBowl.” (If you want to hear more about failure, listen to my podcast series – The MindSide Podcast and episode 1 is on Failure). Imagine if your physician, surgeon, pilot, or military leader never learned how to cope with failure? Upon meeting resistance or adversity, they would lack the necessary skills to persevere. Honestly, I want a pilot that can successfully land in bad weather without much difficulty more than a great pilot that is only comfortable flying in perfect conditions.

Players, coaches, and parents must be comfortable with failure and not be motivated simply to avoid it. The avoidance behaviors only strengthen the fears associated with failure, and then, during competition, players will do what they can to avoid making mistakes or encountering difficulties.

Recently, I led a training session at a NCAA Division I football program with the coaching staff and strength and conditioning team. Our conversation was about strengthening the mental toughness of their players. While the coaches wanted me to give a spirited motivational talk about overcoming adversity, I suggested we turn the challenge to the players. At the end of each training session before our meeting, the players were required to complete 12 “gunners,” where they had to run 110 meters, round the curve of the track for another 100 meters, and then back down the homestretch for a total of 330 meters, allowing a recovery for the final curve by walking back to the starting line. Each position had standards that they had to complete each “gunner” and the coaches tried to motivate them to complete all 12 under that window. During our meeting, the coaches asked me why they could find the reserve in the last one or two, but struggle with the middle four trials. The easy answer was that the players were digging deep to finish strong, but that was the incorrect answer. The truth was that the players were not giving their all in the first 8 or 9 because they were holding back. What we found was that players were “afraid” of running out of gas and not being able to complete the exercise as prescribed, so they were holding back early on and then pushing at the end. Unfortunately, this reinforces the wrong type of mental toughness and effort because they were fearing failure.

So, I changed the protocol. I told the coaches and the players that they would decide how many “gunners” they would run each practice. The only stipulation was that the player had to give full, unbridled effort on each “gunner” and they could choose to stop at any time, without any repercussions. Upon completing their exercise, they had to continue cheering on their teammates but would not be judged by the coaches or strength and conditioning staff.

The results were telling. The first player stopped after the third one and was completely exhausted-an offensive lineman. He was the subject of why this exercise was changed. In the past, he would stride the “gunners” and look like he was giving full effort, but in truth, he was simply conserving to finish. Other players started dropping around the fifth and sixth and some completed twelve, where we stopped the training session, but the overwhelming majority completed between 7 and 10. When we asked the players afterwards if the training was easier or harder, it was overwhelmingly endorsed as being more difficult. The reason – the player had to fight the desire to quit and fail versus giving more effort and finding a way to succeed. The constant battle with failure gave them the tools to learn to be successful. The remainder of the conditioning season saw the team reach new levels of fitness, reduced injuries, and a more successful training camp.

By facing failure directly, players learn to persevere. We as coaches and parents cannot shield our athletes from experiencing the pain and disappointment of losing or struggling, as they are necessary for future success. It is important that these drills and exercises be used accordingly, as they should not be the centerpiece of a training program as confidence is very important to foster as well.

Why Train Failure?

In a training and coaching setting, you have the ability to control the environment and build out a safety net, whereas in competition, you have limited control. You can supplement the failure drills with other experiences that build confidence.

Without adversity, it's almost impossible to build grit or resiliency. An emerging body of empirical literature from Angela Duckworth at the University of Pennsylvania has demonstrated the importance of grit in predicting success across academic settings. If an athlete is never exposed to adversity in training, they will not have the patience, grit, or resiliency to engage the challenge in competition.

To put it another way, renowned talent development scholar and author of The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle, said:

If I were to create a perfect golfer I would start by giving them grit and a growth mindset. It's not the seasoning in this recipe, it's the steak.

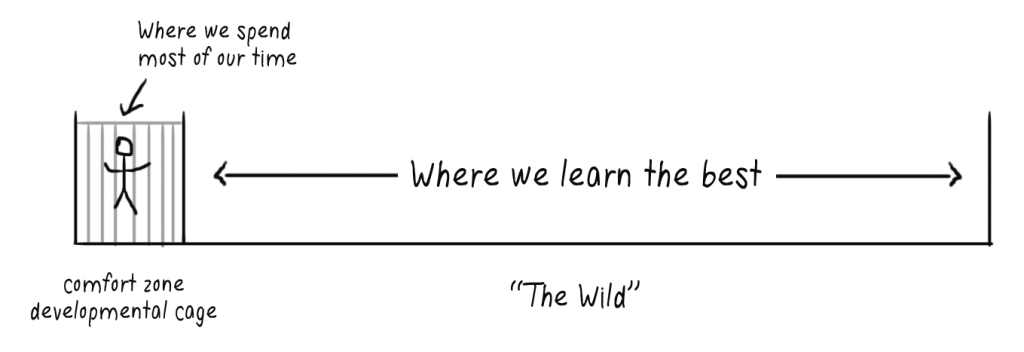

Following the FishBowl approach, humans only grow to the size of the mental boundaries they place on themselves, much like a goldfish only grows to the size of its bowl. Further, people rarely test those boundaries, so athletes will commonly only practice or showcase what they are confident or competent at completing.

I like how Trevor Ragan of TrainUgly.com depicted it in this drawing. Incorporating failure will help you out of your developmental cage!

Finally, failure must always be an option in competition. If failure is not allowed as an option, the behavioral and cognitive approach is often about “failure prevention” and not “goal attainment.” Very simply, the mind does not function its best when trying to limit failure.

What Aspects are Important for Failure Drills?

The drill must be difficult but can be eventually completed successfully with further training and effort. There is no reason to create a challenge that has no ending in it. We, as coaches, are not trying to break them down and lose confidence, so make sure that the drill can be won at some point in the future. The drill must be perceived as do-able as well.

The player should not be aware that they are engaging in a “failure drill.” If they were to know it was meant to challenge their resiliency, more than likely, they would approach the drill differently, and certainly, take away learnings in a different manner.

At a time in the future, the player or team should be debriefed on what that the purpose of the drill was to challenge their resiliency and face failure. I would suggest a time after the players have successfully mastered the drill.

The coach should encourage the players as they would with any other drills, but should not cover up the failure or “sugar coat” it. Instead, a comment such as “Let’s get better and face it again the next time we do it” would suffice.

As with any drill or challenge, review after the attempt as to what they relied upon (e.g., mental skills, past experiences), what they would do differently, and what they focused on during the experience.

Examples of Failure Drills:

For physical training and conditioning, consider drills based on their safety and under the supervision of a professional. I’m challenging my good friends and TPI Instructors Jason Glass and Lance Gill for their expertise with a follow up report.

For golf specific drills, I would recommend the following:

6-Foot Putting Ladder: A great game to develop speed control on the greens in a competitive format.

Alternative Ladder: Place cones or towels in 10 yard increments from 30 yards to 110 yards from the tee. Adapted from drills from TPI Instructor and short game master James Sieckmann, the goal is to run the ladder with as few misses as possible, proceeding with random alternatives of distances. Do not advance sequentially in this drill, but instead as the coach, call out the distances randomly. With more proficient players, you could require a Pass/Fail of two misses, but with less experienced players, you can change the threshold accordingly.

Ladder Drill Chipping: This is a great golf specific drill because it incorporates variability and creativity. The objective is to land the ball at a different distance and allow it to roll out to the hole. Golfers have to challenge themselves by using different lofted clubs.

18 Drives: Have the player select 18 balls and create a stack next to the driving tee on the range. Establish a left and right fairway boundary and have the player hit a drive from their 18 ball stack. For every ball that lands successfully in the fairway, they take another ball out of their stack. For every miss, they take two balls from another stack and add to their remaining stack. The goal is to complete the drill with as few extra balls as necessary.

Now it is your turn – what drills do you have that would be great to add to my example list above? Please email me at bhrett@bhrettmccabe.com to share.

The greatest thing we can do as a coach is to prepare our students for success in the future. Failure is often a painful lesson, but it rarely occurs without learnings for the student and coach.

Don't be discouraged with slips. They are part of the process. Welcome the feedback and make the adjustment. pic.twitter.com/AnBZQZwFHu

— Nilsson Marriott (@VISION54) May 3, 2015

As a parent, it is my opinion that our job is to provide our children with a foundation to exceed our accomplishments. I never want my children to struggle, but also appreciate the importance of them learning how to persevere under my guidance. I have succeeded in my life because I have failed successfully.

Bhrett McCabe, PhD is a licensed clinical psychologist and sports and performance psychologist in Birmingham, AL. Level 1 TPI Certified, he consults with players on the PGA and LPGA tour and is the Sports Psychologist for The University of Alabama Athletic Department. A four year letterman at Louisiana State University in baseball, he was a member of two NCAA National Championship teams and three Southeastern Conference championship teams. He completed his training in clinical psychology with a specialization in behavioral medicine/health psychology, and completed his internship at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, RI. He owns The MindSide, LLC, a performance consulting organization and can be found at www.bhrettmccabe.com