IMPROVE MY GAME

Articles

8 Exercises to Improve your Scapula Stability and Shoulder Mobility for Golf

Poor posture can have detrimental effects on the golf swing. In our previous blogs, we outlined the ways in which prolonged sitting (e.g. at a desk) can lead to poor posture – specifically upper and lower crossed syndromes.

One of the most common misconceptions about good posture is that it means standing as upright as possible with your shoulder blades (scapula) pinched back and forced together. Not only uncomfortable, that position can also be unhealthy for the function of your shoulder joint.

Q. Why is a healthy shoulder joint important for your golf performance?

A. Research shows that the shoulder generates around 20% of total clubhead speed! (Hume et al., 2005)

In this blog, we will explore what good upper body posture means for your golf and provide you with exercises to help increase your upper back strength and shoulder mobility.

Q. Why is upper back strength important?

A. Because beach workouts just won’t cut it for golf!

By beach workouts we mean training bicep curls and chest press in every session! When your upper back is strong, it becomes much easier and more natural to hold yourself in good posture. When you can transfer and maintain that good posture in your golf swing it becomes much easier to produce increased clubhead speed from the forces generated from the ground up.

Training the back and shoulders for both mobility (shoulders and thoracic spine) and stability (scapula and lumbar spine) allows you to:

-

Adequately rotate in your backswing and downswing;

-

Create an explosive stretch-shortening cycle (a.k.a. The X-Factor Stretch);

-

Generate increased clubhead speed;

-

Use effective shoulder and arm movements through impact to help control the clubhead (along with the forearms and hands).

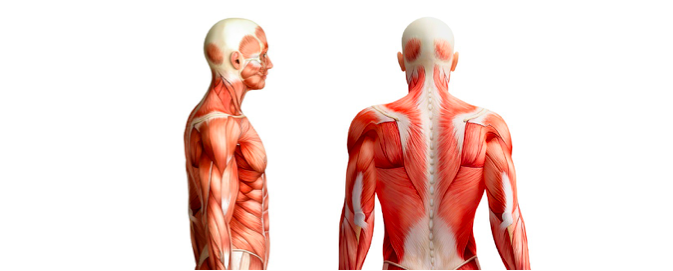

We know that a certain amount of external shoulder rotation (turning the upper arm outwards) is needed during the golf swing in both the trail and lead sides. The anatomy and physiology of the body dictates that in order for this external shoulder rotation – and indeed other shoulder movements – to be optimised, the scapula needs to be stabilised by muscles including serratus anterior, rhomboids, levator scapula, and trapezii (Pain & Voight, 2013).

“The scapular muscles must dynamically position the glenoid* so that efficient glenohumeral movement can occur.”

(Pain & Voight, 2013, p.618)

*Note: The glenoid is the scapula cavity which along with the humerus (upper arm bone) creates the glenohumeral joint

This dynamic positioning is especially true in the golf swing where an appropriate scapula position is required to optimise the transfer and generation of force during the swing (Mackenzie et al., 2015). This is because the scapula is a key component of control in the kinetic chain (i.e., generating force from the ground upwards, through the pelvis, torso, arms and ultimately the clubhead. Many of you will know this as the kinematic sequence) (Sciascia et al., 2016; see Lamb and Glazier, 2017 for a full review of body segment sequencing in golf). As we stated earlier, previous research has already told us how the shoulder generates around 20% of total clubhead speed (Hume et al., 2005)!

While the exercises below are designed to help you to work on the stability of the scapula and mobility in the shoulder, you should be aware that if there are dysfunctional links lower down in the kinetic chain then these will also need correcting to help you swing that golf club as fast as you possibly can.

“Impairment of one or more kinetic chain links (anatomical segments) can create dysfunctional biomechanical output…When deficits exist in the preceding links, they can negatively affect the shoulder…programs focused on eliminating kinetic chain deficits and soreness should follow a proximal-to-distal rationale where lower extremity impairments are addressed in addition to the upper extremity impairments.”

- (Sciascia et al., 2016, p.317).

For this reason, it’s important to work with both a golf coach and a golf fitness trainer / strength and conditioning (S&C) coach to identify and address any impairments that might be limiting the full potential of your swing.

Research tells us that shoulder issues can be linked to limited scapula stability, rotation and position (see Mackenzie et al., 2015 for full review), but this golf specific research also highlights that golfers will often present asymmetries between their trail and lead scapulae’s upward rotation in the coronal plane. For all the trainers/S&C coaches reading this: Be aware that the researchers, who studied 45 European Challenge Tour golfers, also stated that this does not indicate increased risk for injury and is perhaps just due to the varying demands placed on each shoulder and scapula during the different phases of the swing over prolonged participation in the sport (Mackenzie et al., 2015). However, this asymmetry should not be trained into golfers in a strength and conditioning programme!

As we mentioned, faking good posture by simply pinching your shoulder blades together may make you look taller in the short term, but can be exposed by the force generated in your golf swing. It’s time to build up the strength, control and mobility you have around this area of the body so that you can spend more time playing golf and less time thinking about holding yourself upright.

Check out these videos of some great exercises to help you work on the points we have discussed above…

Scapula Wall Slides – facing the wall

This exercise is a regression from the back to the wall scapula wall slides.

The aim here is to keep the forearms in contact with the wall as you slide them up and down. You should feel the scapula rotating around the rib cage as you can see in the video. The arms should never quite get to full extension at the elbow as that draws the focus away from the upper back.

Wall slides can help to increase shoulder mobility, activation of the upper back muscles, and scapula stabilisers.

2-3 sets of 30-60 seconds.

Scapula Wall Slides –back to wall

Scapula Wall Slides –back to wall

This exercise is a progression from facing the wall. It again benefits shoulder rotation, activation of the upper back muscles, and scapular stabilisers.

Keep the head, upper back and forearms in contact with the wall throughout. Before you begin sliding the arms you should tip the pelvis backwards to reduce the curve in the lower back – i.e. try to flatten the back on the wall.

Progress through wall slides is generally quick and therefore the next exercise adding some resistance will help to maintain overload and progression.

2-3 sets of 30-60 seconds.

Mini-Band Wall Walks

A point to bear in mind when working on scapula stabilisation is that if the resistance you select is too heavy then the shoulder will likely shrug causing the prime movers to take over the movement and not effectively work the intended stabilising muscles (Coffel and Liebenson, 2017).

Therefore, select a mini-band that allows the shoulder to stay down while your forearms walk up the wall. Keep the spine neutral and the forearms parallel to each other throughout.

Begin with 2-3 sets of 5 walks up and down the wall with 2-3 minutes rest between sets.

Mini-Band Arm Raises

Keep a stretch on the band throughout and maintain the position of the palms (facing each other) throughout the movement. When your arms get to the point of full extension at the elbow pull them apart even wider and raise overhead. Hold for a count of three and then return to the start position. Taking your time through this movement will lead to benefits in both scapula stability and shoulder mobility.

Begin with 2-3 sets of 5 arm raises with 2-3 minutes rest between sets.

Half-Kneeling Landmine Overhead Press

This great exercise benefits thoracic mobility through the anti-rotation core stability work involved. It also acts to increase the dynamic stability of the scapula.

Use a landmine or a free plate on the floor to place the bar in. Brace the core to keep the body still with no rotation or extension as you press the bar up straight out from the shoulder to a fully extended arm. Maintain good neutral posture throughout.

Begin with 2-3 sets of 10 reps on each side using your 10 Rep Max (10RM).

2-3 minutes rest between sets.

Bent Over Row with Barbell

In this exercise the posture of the upper body is very important. The spine should be in a neutral position throughout. Make sure the upper body is bent over from the hips in an almost horizontal position – how close to horizontal you get dictates the muscles that are worked on during this exercise. These can include the lats, rhomboids, posterior deltoids, traps, and biceps.

As you row towards the lower ribs make sure nothing moves apart from the arms.

Begin with 2-3 sets of 10 reps using your 10 Rep Max (10RM) where you can still maintain form.

Reverse Flyes

Reverse flyes target the strength of the posterior deltoid, the rhomboids and the traps. Again, in this exercise the posture of the upper body is very important. The spine should be in a neutral position throughout. Make sure the upper body is bent over from the hips in an almost horizontal position. As you complete the flyes ensure the chin stays tucked in with the spine in neutral so that you don’t do any pigeon head movements! As with the bent over row – nothing moves apart from the arms.

Begin with 3 x 10 reps using your 10 Rep Max (10RM) where you can still maintain form.

2-3 minutes rest between sets.

Plank Mini-Band Walks

A great exercise to work on core stability through anti-rotation, upper back and shoulder strength. Assume a plank position and imagine there is a + on the floor beneath you. Walk your hands along each line of the imaginary + (forwards, backwards and to both sides) while minimising rotation of the hips and torso.

Repeat two cycles for every set and complete 4-6 sets with 2-3 minutes rest between sets.

We hope you enjoy these exercises. Here’s to improving your posture and your golf in 2018.

Be sure to follow us on Twitter for more golf fitness tips:

Dr. Ben Langdown was head of Sports Science at The PGA National Training Academy at The Belfry for over 10 years and is now lecturing and researching in Sports Coaching at The Open University (@OU_Sport). Alongside this Ben works with many elite amateur and professional golfers providing strength and conditioning support. Ben has a PhD in the field of golf biomechanics, studying movement variability and strength and conditioning for golf. Having previously presented research on golf swing centre of pressure displacement and warm-up protocols at two previous WGFS, his most recent research has focused on the relationships between physical screening and 3D golf swing kinematics. Follow Ben at @BenLangdown.

Jennifer Fleischer is the founder of Holistic Fitness San Francisco, a wellness consulting company that offers Golf Fitness Training, Strength and Conditioning Programs and Integrative Nutrition Coaching. She is a Level 3 Titleist Performance Institute Certified Golf Fitness Instructor. Follow Jennifer at @HolisticFitSF.

References:

Brody, L. T., & Hall C. M. (2010). Therapeutic Exercise: Moving Toward Function. (3rd edn), Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health: Philadelphia.

Coffel, L., & Liebenson, D. C. (2017). The Kettlebell Arm Bar. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 21(3), 726-738.

Hume, P. A., Keogh, J., & Reid, D. (2005). The role of biomechanics in maximising distance and accuracy of golf shots. Sports Medicine, 35(5), 429-449.

Lamb, P. F., & Glazier, P. S. (2017). The Sequence of Body Segment Interactions in the Golf Swing. In M. Toms (Ed.) Routledge International Handbook of Golf Science (pp. 24-32). Routledge: Oxon.

Mackenzie, T. A., Herrington, L., Funk, L., Horlsey, I., & Cools, A. (2015). Sport Specific Adaptation in Scapular Upward Rotation in Elite Golfers. Journal of Athletic Enhancement 4(5), 1-6.

Paine, R., & Voight, M. L. (2013). The role of the scapula. International journal of sports physical therapy, 8(5), 617-629.

Sciascia, A., & Monaco, M. (2016). When Is the Patient Truly “Ready to Return,” aka Kinetic Chain Homeostasis. In J.D. Kelly IV (Ed.) Elite Techniques in Shoulder Arthroscopy(pp. 317-327). Springer International Publishing: Cham.