IMPROVE MY GAME

Articles

Solving the Middle Man

It wasn’t so long ago that talking about the function of the thoracic spine region drew puzzled looks from even highly dedicated trainers and teachers. I was no exception. Thanks to efforts from some talented people, including TPI’s co-founders, the thoracic spine has gone from bit player to the spotlight, and rightly so. Without reasonably sufficient t-spine movement, the golf swing suffers. Let’s take a deeper look into why that’s the case.

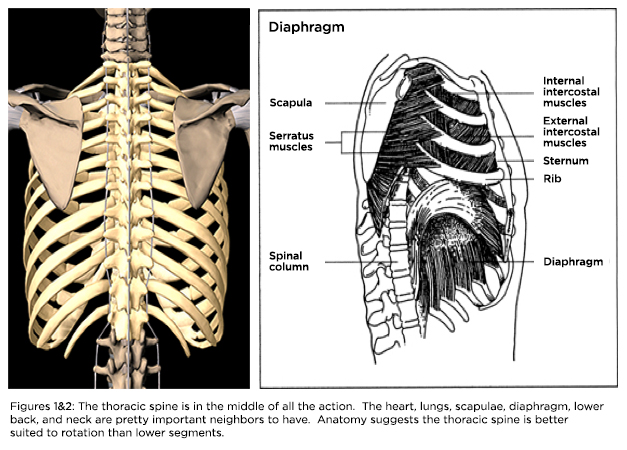

It’s important to get everyone on the same page with a brief anatomical overview of the area. Luckily, a picture is worth a thousand words (figures 1&2).

Four key performance joints surround the t-spine: the lumbar spine (lower back), cervical spine (neck), and two scapulo-thoracic joints. It’s not an accident that all four of these areas have a premium on stability. That suggests t-spine and ribcage mobility are oh so important.

Pouring over research on golf injuries (e.g., Cabri et al., Eur J Sport Sci, 2009 and more), most injuries in both amateurs and professionals tend to occur in the following regions:

- LOWER BACK

- SHOULDERS

- ELBOWS

- WRISTS

According to the aforementioned review of golf injury studies, the two principle risk factors for golf injury are age and low handicap. It’s safe to assume low-handicappers play and practice more to achieve increased skill. Therefore overuse, owing to either age or repetition, appears to be a common factor in golf injury risk. If we examine the location of frequent injuries, they virtually surround the thoracic spine. (Since the elbow approximates a simple hinge, many believe the true source of elbow overuse injuries is at the scapulo-thoracic joint.)

As one of my mentors Mike Boyle says, “when you see an overuse injury, look above or below for the cause.” One can imagine how a poorly moving thoracic spine can force movement to happen at adjacent areas. Repeated thousands of times, such compensation is a recipe for trouble. This is what makes the joint-by-joint theory so practical, and directly applies to the golfers you work with.

Stiffness in the thoracic spine has often overlooked consequences beyond overuse injuries. A trusted routine and consistent swing tempo are widely considered critical to golf performance. The rhythm of breathing can either reinforce or disrupt these keys. Hunched shallow breathing can promote rushed routines and swings. Likewise, a few deep breaths can help re-focus the mind to the task at hand. A good caddie has known this for years.

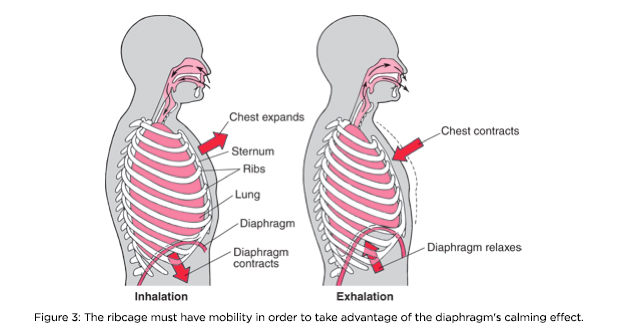

In fact, deep belly (aka diaphragmatic) breathing can change physiology from sympathetic (fight/flight) to parasympathetic (rest/digest) responses from the autonomic nervous system. However, that breathing style requires mobility in the ribs. (To inhale the first rib must elevate and the thoracic wall expands to create a relative vacuum inside the thorax - see fig. 3.) Since most of the ribs are connected to the thoracic spine via cartilage, there is some give and also helps explain why some people become very sore after t-spine mobilizations.

Stiffness in the thorax can alter our posture and change the orientation of the diaphragm. This compromises its ability to function. Importantly, the diaphragm does more than affect inhalation. The diaphragm also connects to the lumbar spine, psoas major, and abdominal wall muscles. Therefore, movement and posture of the thorax is a key piece in connecting the upper and lower body. If the thorax is stiff, our ability to stabilize the lower spine and maintain posture can be compromised. It’s safe to say most golf coaches want their students to maintain posture and transfer energy from the lower to upper body. As industry giant Gray Cook preaches, “mobility before stability.”

The goal of this article is to emphasize why the t-spine is important to golf. Efficient rotation, breathing, posture, and durability are pretty solid reasons. The t-spine has more implications but it’s safe to stop at this point because two questions likely jump to mind:

- How can I tell if a golfer/athlete has t-spine dysfunction?

- What can I do to help him or her?

Multiple TPI and FMS screens investigate the t-spine. The screens can be done in 5-10 minutes and yield valuable information about the person standing in front of you. There is no need to re-invent the wheel so screen your athletes! Below are a few TPI screens that test t-spine function.

Seated Truck Rotation

Torso rotation

Overhead Deep Squat

Lat Test

Likewise, plenty of videos for t-spine mobility and breathing exist on the TPI site and others. I’ve incorporated a few of my favorites at the end of this article but there are many more on the TPI site. Just use the advanced filter/search in the TPI exercise library and select thoracic spine for the body part. In my experience, the exact exercises chosen are relatively unimportant. The quality of the drills’ execution is far more important because we must integrate posture and breath. Below are some observations and tweaks I’ve found useful:

- Watch the facial expression and breath of your athlete. If he/she is wincing, tight-jawed or shoulder breathing, then the drill has been taken too far or posture is off. More isn’t always better.

- Our best results start with the athlete on his/her back (supine) with bent knees and hips. This reduces the load on the spine and helps narrow awareness to breath and posture.

- People tight in the t-spine will try to move from the lower back and neck. Try to find positions and drills where that option is limited. Flexing the hips so the knee is parallel to the pelvis is a common tip. Making a long neck with tucked chin is another useful cue.

- Rather than worry about sets and reps, try counting full breath cycles; a full belly inhale through the nose, full exhale (getting all the air out), a 2-second pause, and repeat. 3-5 of these cycles are a good starting point and will get your type A folks away from the obsession over racing through everything.

- You should see an immediate benefit. It may not be world-changing but if an athlete isn’t full of plates, screws, and titanium, you should see something within a few minutes. If not, find another drill or improve the quality of the one you did. This means re-screening is a valuable practice. Not only does it confirm your approach, your clients will love to see progress.

I think one reason this crucial area tends to get lost in the shuffle is because it’s not often symptomatic, certainly not relative to the areas above (neck) and below (lower back). As our paradigms rightly shift to value causes rather than chase symptoms, the t-spine has ascended to become a central hub of movement analysis. Given golf’s coordination demands of so many body parts, the t-spine is worth consideration in the gym or on the driving range. It’s simple to test and can often be quickly improved. That makes it a great candidate for improving your players and your business.

Foam Roller Spine

Brettzel

Open Books

Prayer Stretch

Max Prokopy is lab coordinator of The UVA SPEED Clinic motion analysis laboratory at The University of Virginia. He holds multiple degrees and certifications in the field of human performance. He spends most of his time using 3-D motion capture and biomechanics to help golfers and runners of all abilities.